Many people in our region are familiar with Emily Williamson’s work and may be completely unaware of that fact. But if you have ever been to the town of Floyd you have more than likely seen her work in some shape or form. Whether it was her banner for one of the earlier Floydfests or a playful graphic on a t-shirt at The Republic of Floyd, it is likely that anyone familiar the art scene there has come in contact with some of this multi-talented artist’s work. Immediately intrigued by her style when we first saw it, we did a little research and found that Emily is somewhat of a celebrity artist in her hometown… but we were curious to know what she creates when she is not limited by the boundaries of a commissioned piece.

VIA: Tell us about your education in art. When did you begin creating and did you receive any formal training?

EMILY: As a child I was always a little bit better at art than the other kids, and I was aware of that. I won a couple of little contests when I was small. Somewhere around middle school, a time when people come to a point where they either drop art or continue with it, I realized that I had the ability to capture a likeness of people. I started out with black and white pencils as my medium of choice. When I was in high school I realized that I had some power with my artistic abilities and I could use it as a tool to get attention from my classmates. I started drawing pictures of rock stars that I was into from photos in Rolling Stone Magazine.

I went to VCU for art but after the first semester I dropped out and lived with a friend and a couple of other people for a year. After that my family convinced me to go back and give it another shot, so I went for one more semester, but I was a country girl in the city and didn’t really know how to deal with life there at only 18, 19 years old. I did pick up some skills and knowledge from there but I didn’t complete a degree. There’s a lot to learn about art but I already know how to do what I do. Since then I’ve just been working for myself doing commissions.

VIA: What is your favorite medium to work with?

EMILY: I prefer to use acrylic paint over oil because oil doesn’t dry fast enough for me and I can go over the layers of a piece I’m working on sooner with acrylic paint. I spent many years doing pastels and I really enjoyed that, but I got out of working with them. In recent years I haven’t done much pastel work, I guess in part because it’s expensive to frame your work and pastels don’t last as long, it’s crumbly and dust falls off, so I’ve been working mostly with acrylic for about the past seven years.

VIA: Tell us about your work doing commissions.

EMILY: I’ve been doing a lot of commissions for a long time now, because I’m trying to make my living as an artist. I’m a very versatile artist. I don’t just do portraits… that’s just something I have a knack for and enjoy; I’m capable of a lot of different styles. I’m good at taking people’s ideas and seeing them and translating them, so I’ve gotten all sorts of different commissions.

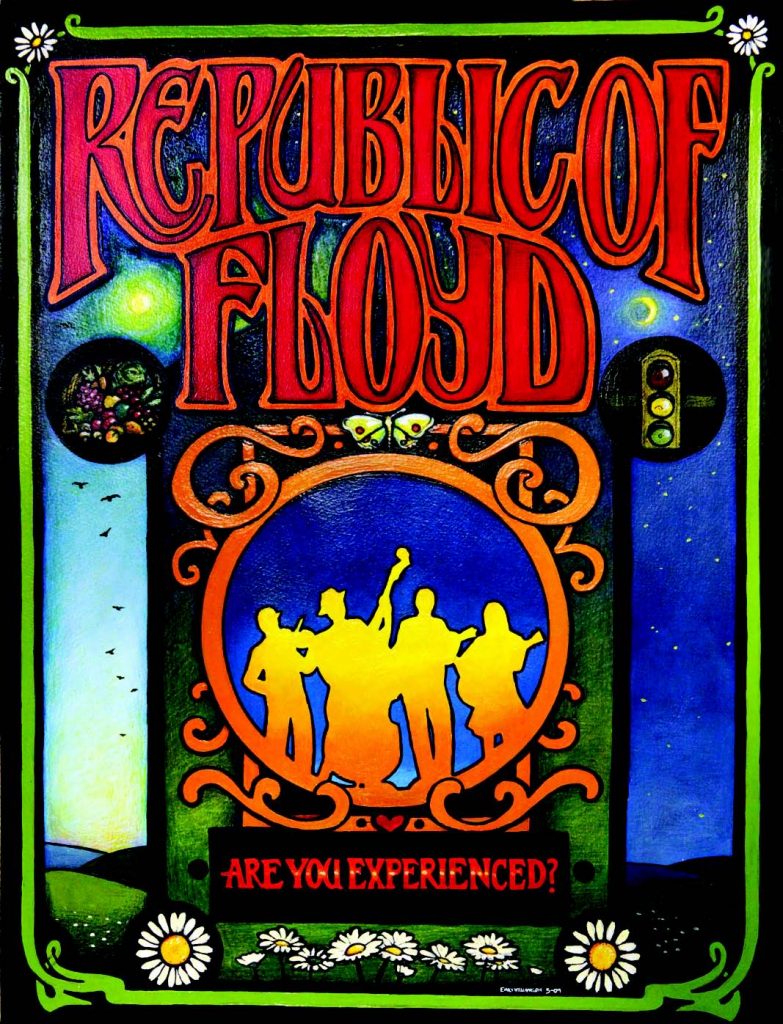

The Republic of Floyd Emporium commissioned me to do these ideas that Tom Ryan, the owner, comes up with and he puts them on t-shirts, coffee mugs, key chains, a whole handful of stuff. There’s a Jethro Tull poster that I used the framework of for a piece that was about the Republic of Floyd, with a bluegrass band in the center instead of Jethro and his flute.

I enjoy meeting the challenges people give to me but I’ve gotten kind of stuck in having art being my moneymaker and accepting jobs that people come to me with offering money and say, “draw this for me.” I don’t follow that inspired feeling to the end result; I force myself to sit down and finish. So I’ve been doing a lot of this sort of forced artwork for several years. I’m a single mom, so I just have to make it work.

VIA: What influences the work that you create when you’re not doing a commissioned piece?

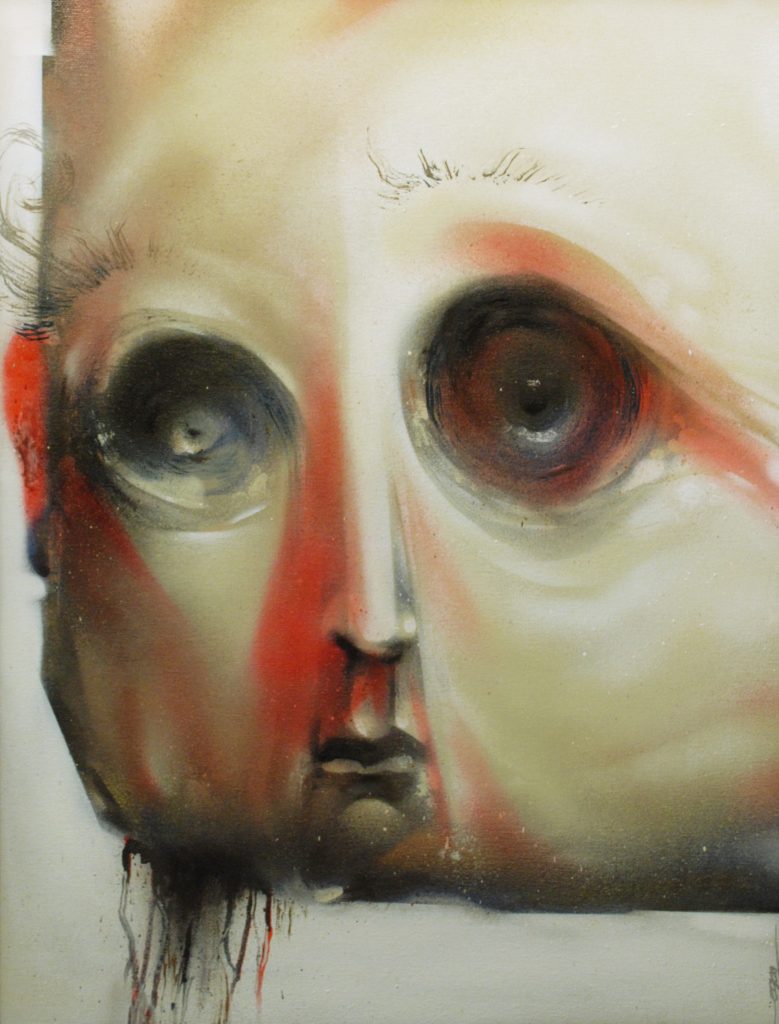

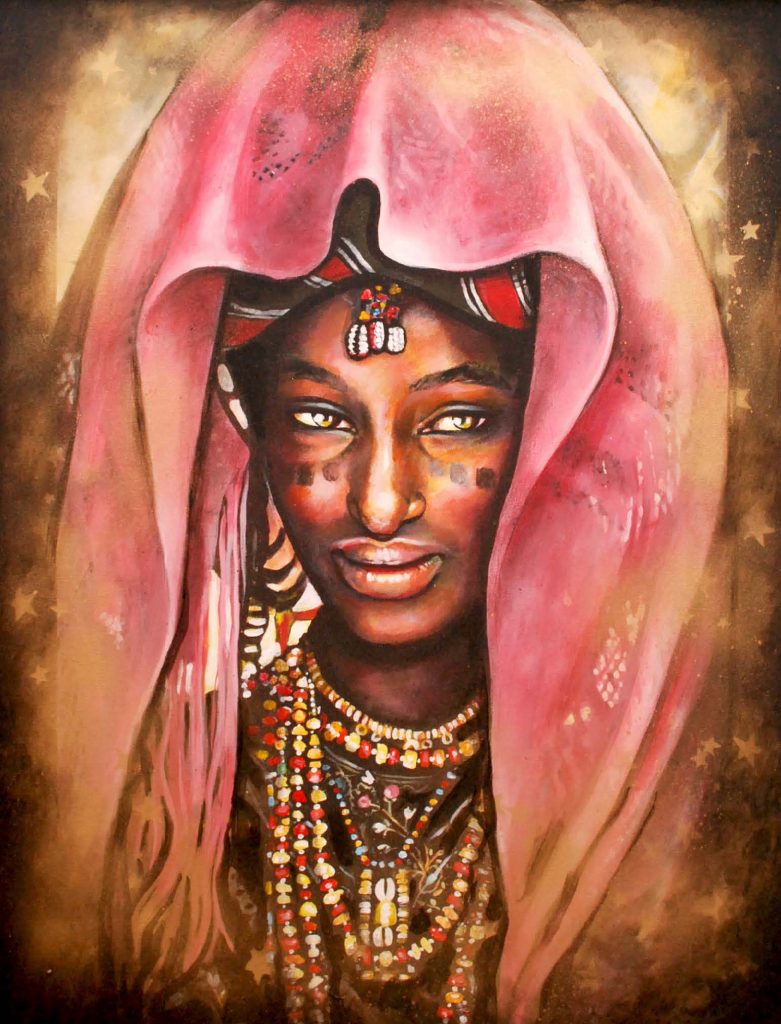

EMILY: When it comes to things that I’m inspired to create… lately I’ve stopped accepting so many commissions and I’ve only started accepting the ones that I really care about. I have always enjoyed doing portraits; I feel like I’m spending time with the person that I’m doing a drawing of. I feel like it’s a chance for me to delve into someone’s energy that way.

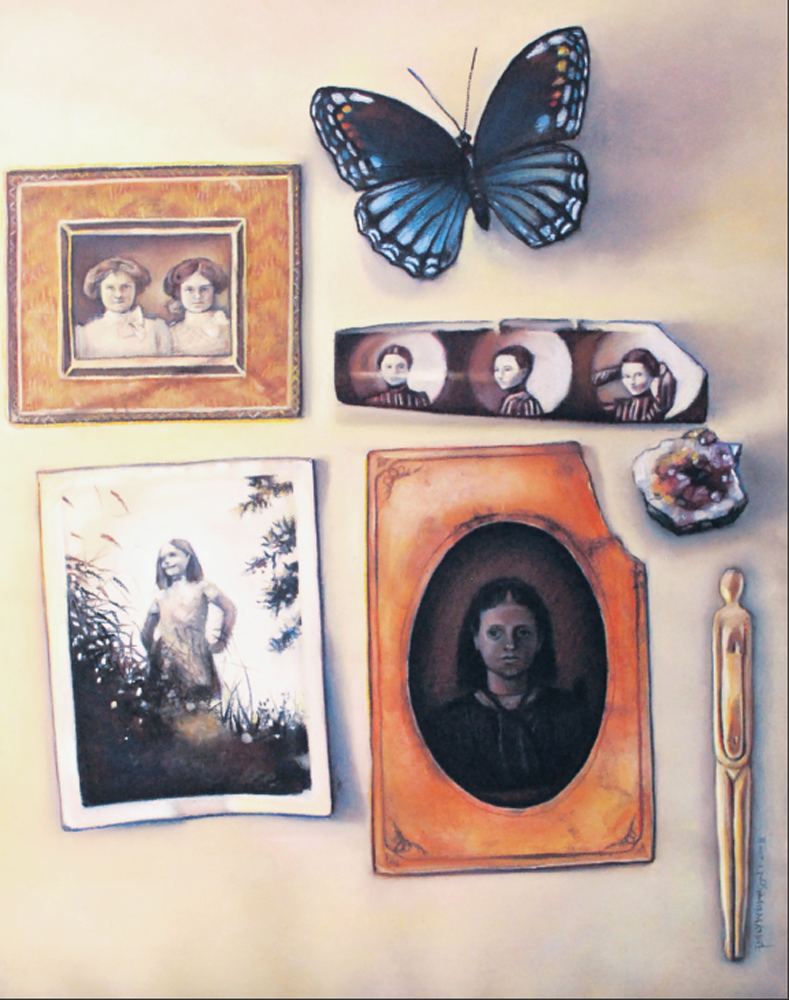

I like to do lots of pictures of my friends. I’m a nature girl, my friends and I like to go out and do lots of photo shoots surrounded by nature. I think my friends are beautiful and the photos from our shoots inspire me so I render them and use them as inspiration for my work. They all get a little slice of immortality that they don’t mind too much. My I’ll Miss You piece is from one of our photo shoots. It’s of one of my best friends, Leia, that I dance with as well; we hiked up to the top of a waterfall (Alta Mons in Shawsville) and went in the woods and into the water. The piece is of her from the back with a veil draped over her and walking away, like into the great beyond, but it’s very focused on the ripples in the water.

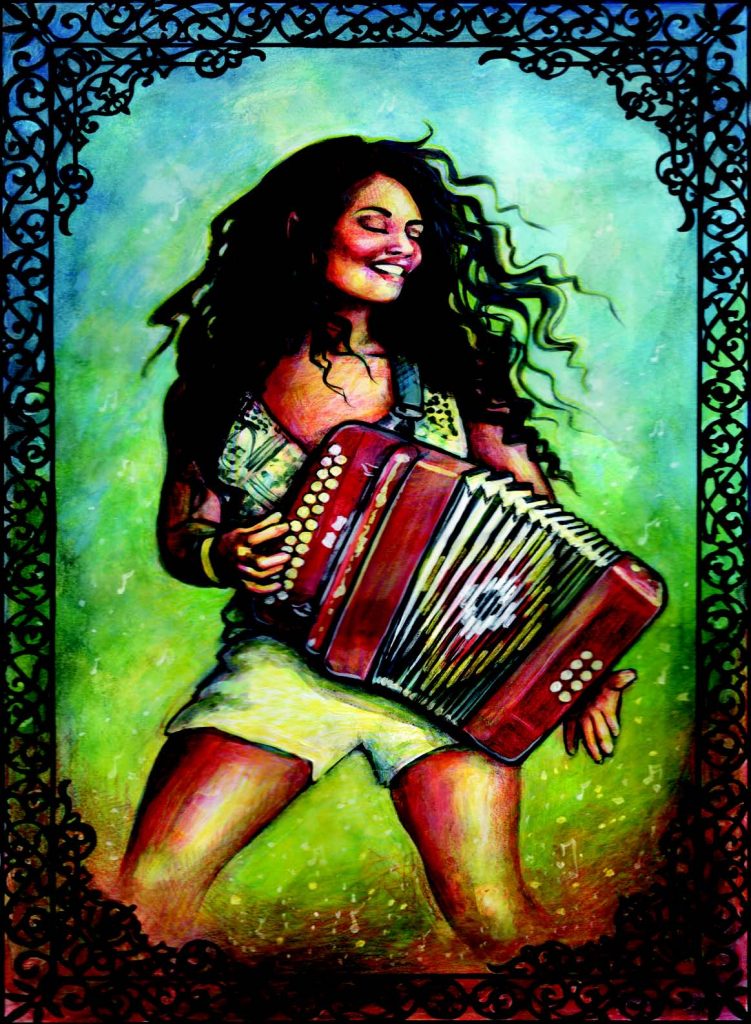

Pictures of performers, musicians, dancers, people in costumes are subject matters that I would like to get into more. I’m interested in circus performers and that whole imagery. I usually like to work from photographs rather than to live paint, although I like to do that too.

VIA: Is your work displayed anywhere else at the moment, other than at The Republic of Floyd?

EMILY: I submitted a couple of pieces to the Jacksonville Center’s September juried show. I have a couple of things in the Bell Gallery in Floyd. But for right now, I’m really working to create this whole new line. I’ve only recently come to this new place where I have a scrap of money and can relax and try to rediscover myself as an artist.

VIA: Do you feel like you are well supported by the art communities around you?

EMILY: I feel like I’m well supported in Floyd. It’s not often that a person can make a living off of their artwork but I did make a living for quite a while off of commissions just in Floyd. And it’s cool that Tom Ryan built his brand around my images for The Republic of Floyd. As for support in Roanoke, I’ve had a great response. The people at Cups Coffee & Tea in Grandin have been very supportive and invited me to come back any time. There was a frame shop and gallery where I showed a guy my card but he was looking for something more edgy. I don’t think I’ve tried hard enough to put my art into Roanoke. But as far as I can tell Roanoke is pretty welcoming; I don’t see an incredible amount of difficulty to get in.

VIA: Are there any other facets of your life you believe readers will find interesting about you?

EMILY: I sing with a band; we call ourselves The Unapologetics. I’m also part of a [belly] dance group with several of my friends. I enjoy dance, choreography, costume making, singing; sort of all of these similar creative things.

My dad, Seth Williamson, was a radio announcer who was based out of Roanoke. He passed away in October. He was the Morning Classics guy on 89.1. He had a couple of other shows, like Bluegrass & Americana. He was very much a nature guy too, which I think trickled down to me.

VIA: How can people contact you if they are interested in your work?

EMILY: I’m on Facebook and can be reached by my email address at smellslikedirt@gmail.com.

This article was originally published in the second issue of VIA Noke Magazine, printed in Roanoke, Virginia in July 2012.