After introducing himself, Chad opened his black carrying case to reveal a colorful display of his work. Inside were glass marbles and pendants containing tiny galaxies of twisting colors and shapes, some enveloping small pieces of opal.

Chad has always been fascinated by glass. “You go to Williamsburg and you see them working in the furnaces, but I never really knew much about [the process].” While shopping around for different beads, Chad and his wife began to notice the differences in quality and features of glass pendants. After seeing an advertisement for a glassworks show that was coming to Philadelphia, they decided to go and attended a lampworking class. “We liked it so much that we went out of the class, bought a torch, bought a kiln, bought a bunch of glass, and we’ve been working ever since.”

“Most of my pieces are about ninety percent clear glass. While it’s hot I do what’s called fuming; I take a piece of fine silver or 22-carat gold and put it in the flame and it vaporizes.” The fumes collect on the glass creating the various colors you see inside of a piece.

He held up a flat pendant with an opal inside. “Something like this starts out as just a clear, hollow tube and I drop the opal down inside it, melt it down, make it solid, and then add colors around it and build it up. When it’s finished it’s actually twice this size. I have a grinding machine that I use to grind off the front half which reveals down to the clear glass.”

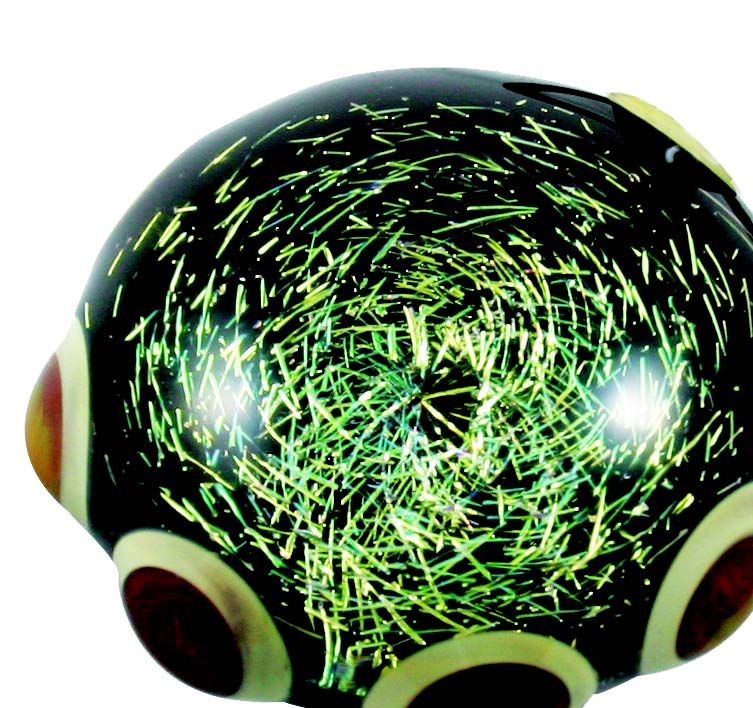

To achieve the metallic rainbow effect he uses dichroic glass, a special type of glass created by NASA that contains various metals and oxides. “When you look at dichroic glass before you use it, it doesn’t look anything like this; it just looks like glass that has a little bit of a tint to it. When you get it hot and twist it the coating breaks up and splinters and makes these patterns.”

When we asked how he planned out a piece he was about to create, he explained that it was much more complicated than that. “When I first started I used to make things just to see what would come out, but now I know that if I combine [a certain] color with [a certain] technique, I have a pretty good idea of what the result will be. I have the advantage that I can work with much more detail that the furnace workers can, but they can work a lot larger than I can.”

“With dichroic glass, you can’t always tell in raw form what color the finished piece is going to be.” He picked up two distinctly different pendants to demonstrate his point. “This one and this one came off the same sheet of glass. It just depends on where the chemicals are on the glass, because there could be different ratios of metals on different parts of the sheet. So sometimes I’ll work on it and let it cool a little bit to see what color it’s going to be. But glass doesn’t like to heat up and then cool down quickly. This glass likes to either be at room temperature or completely molten and nowhere in between, so you have to really watch it.”

“Just educating the buyer,” he says, is “part of the struggle.” Before meeting with Chad, many people do not understand the materials, process, and hard work that goes into making each piece. “I have a daughter who is really into art and I’m trying to educate her on why art costs what it does. Some of these probably only have about $5 worth of glass in them, but I have [put in] two hours worth of work. Somebody asked me once at a show, “How long does it take you to do something like this?” I said, “Well, it takes about two hours and eight years,” because I’ve been working for eight years to get to this point.”

If you are interested in seeing more of Chad’s work, you can find it at Gallery 108 in Downtown Roanoke, A Little Bit Hippy at Towers Mall, and The Little Gallery at Smith Mountain Lake in Moneta.

This article was originally published in the first issue of VIA Noke Magazine, printed in Roanoke, Virginia in May 2012.